- Last Updated

- Posted by

- Childbirth, Pain Control

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2010. All rights reserved.

Ernest (“Jack”) Hilgard is one of the most important and well-known figures in the history of hypnosis. He was professor of psychology at Stanford University in the USA and an authority on hypnosis and the relief of pain. With his colleague Andre Weitzenhoffer, Hilgard also developed the most widely-used psychological measure in the field of hypnosis research, The Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS). Hilgard dedicated a chapter to reviewing the research evidence on hypnosis and clinical pain in obstetrics in his seminal Hypnosis in the Relief of Pain, co-authored with his wife Josephine Hilgard, first published 1975 but revised in 1994. Most the research cited by Hilgard is very dated now, and comes from the 1960s or earlier. More recent studies have, of course, generally employed more reliable research design. Nevertheless, due to the limited amount of information available in this area, some of these findings are still of interest and, as a leading authority on the subject of hypnotic pain control, Hilgard’s comments and analysis are of some lasting value.

Hilgard described the landscape of natural childbirth methods, and the methods under comparison, as follows,

There are three principal methods by which the expectant mother may prepare for her confinement in the hope that the delivery will be comfortable without the use of drugs: (1) hypnotic procedures; (2) the method known as natural childbirth, introduced by Grantly Dick Read in 1933; and (3) the procedures associated with the psychoprophylactic method, introduced in Russia by Velvovski in 1949 and rather widely used in France and elsewhere, often called the “Lamaze method” in America, after the man [Dr. Fernand Lamaze] who helped bring it to France. The three practices overlap in many ways, leading some to believe that they are practically indistinguishable. We recognise the overlap but think it is a mistake to gloss over the difference. (p. 103)

Hilgard notes that the Lamaze method, which is derived from the Soviet psychoprophylactic method, ultimately evolved out of Pavlovian hypnotherapy for childbirth. Dick-Read was more ambivalent toward hypnosis and although he made extensive use of muscle relaxation and verbal suggestion and reassurance, he generally tried to distance his method from hypnotherapy. In contrast to Dick-Read, Hilgard thought that the notion of painless childbirth in primitive societies was probably a myth but agreed with those who argued that anything that reduced the need for chemical analgesics or anaesthetics was likely to reduce risk to the mother and baby.

The Read method has three main elements: factual instruction regarding childbirth; physiotherapeutic practices, especially relaxation and breathing exercises; and psychological methods that inspire confidence and carefully incorporate suggest (but avoid hypnosis). (p. 105)

William S. Kroger, a well-known hypnotist and obstetrician, had earlier questioned whether Dick-Read was right to distinguish so sharply between his method and hypnosis (or self-hypnosis) and Hilgard also notes that this distinction needs to be verified. However, sometimes the Dick-Read method has been described as a more “physiotherapeutic” approach because of the emphasis it places on different forms of muscle relaxation and breathing exercises. It should be emphasised that the aim of some of these approaches is primarily to improve the quality of the childbirth experience overall rather than to eliminate pain completely. However, pain management is obviously a major area of interest to both parturient women and researchers alike, and the main focus of Hilgard’s book.

Non-Hypnotic Methods

By the time of Hilgard’s review, several large studies had already been published on the Dick-Read method of natural childbirth. In these studies, about one quarter to one third of women prepared by Dick-Read’s method required no chemical pain relief during labour, which was better than women who received no training. Those women trained in the Dick-Read method who did require some pharmaceutical pain relief, who were in the majority, generally used less than unprepared women.

However, this seems like a relatively modest achievement as a recent, more carefully designed review found that over a quarter of women were able to give birth without chemical pain relief, under normal conditions, without any preliminary training. The same study found that 62% of women receiving hypnosis were able to do without chemical pain relief during labour, seemingly a substantial improvement on the Dick-Read method or “no treatment”. However, Hilgard felt that overall the data “strongly support the conclusion that relief does occur for some fraction of the women prepared by the [Dick-Read] method.”

The method that has largely supplanted the Read method in the United States is known as the Lamaze method, or psychoprophylaxis. Its history as an outgrowth of hypnosis is worth recounting. Fernand Lamaze, a French obstetrician, visited Russia and brought the method back with him to France in the 1950s. By becoming a vigorous spokesman for the method and successfully promoting it in France, England, and the United States, he has given his name to it. (p. 106)

As Hilgard points out, the Lamaze and psychoprophylactic methods were derived from the hypnotherapy (“hypnosuggestive”) approach developed by K.I. Platonov, director of the School of Psychotherapy in Kharkov, which became increasingly popular from 1936 onward, when Platonov summarised his use of hypnosis for pain relief in 588 cases, with a reported success rate of about 60%. From this point onward, hypnotism was used on a massive scale in the Soviet Union, with special “hypnotariums” being established in major cities like Leningrad and Kiev. Hilgard notes that one Russian study reports that details of 8,000 cases of hypnotic pain relief in childbirth were published during this period.

The new method, psychoprophylaxis [meaning “psychological prevention” of pain during childbirth], grew out of the favourable experience with the hypnosuggestive method. It was originated by Velvovski and was officially sanctioned by the Ministry of Health of the Soviet Union in 1951, in a publication called Temporary Directions on the Practice of the Psychoprophylaxis of the Pains of Childbirth. (p. 106)

Hilgard sums up Lamaze’s version of the psychoprophylactic method as follows,

As adopted by Lamaze and his followers, psychoprophylaxis tends to be objective and specific in its teachings, although there is a strong component of suggestion throughout the sessions. Teaching includes what happens in the course of a normal pregnancy; the Pavlovian thesis of relieving pain by eliminating fear; respiratory exercises; neuromuscular control through relaxation; and the appropriate responses during labour and delivery. An important aspect of the process is participation of the expectant mother throughout. The training commonly includes the father, who becomes a participant also. (p. 106)

Hilgard reports a controlled study conducted on the French psychoprophylactic method, as follows,

A careful test of the effectiveness of psychoprophylaxis as practiced in France was conducted by Chertok and his associates. The total study involved more than 200 women, but complete data were obtained throughout pregnancy and confinement for 90 of these prepared by psychoprophylaxis and for 26 unprepared women who constituted a control group. On the basis of a score derived from the “goodness” of the confinement, 49 percent of the prepared women achieved a “good” confinement, as compared with 27 percent of the unprepared group. The prepared women also reported somewhat less pain. (p. 107)

It’s impossible to make a direct comparison but broadly speaking, it seems a slightly better result for Lamaze than was found for the Dick-Read method. In the French study, women trained in the Lamaze method were almost twice as likely to be rated as having a “good” childbirth, from a medical standpoint, compared to unprepared women.

Hypnotic Methods

Hilgard provides some examples and discussion of typical hypnotic method. He rightly points out that, of course, preparation for childbirth can take place over several months and involves anticipation and potentially rehearsal of the event of birth itself. Hypnosis is particularly good at helping people to imagine themselves being in another situation, e.g., as in hypnotic age regression. Hilgard observes that in preparing for childbirth, “rehearsals may be given greater reality by being carried out under hypnosis.” This is potentially a major advantage over other methods and imaginative rehearsal may be more important than relaxation, despite the emphasis placed upon relaxation in various methods. Hilgard cites an interesting component analysis study, which attempts to settle the question over the extent to which relaxation contributes to hypnosis for childbirth,

The exact influence of various components of training is hard to assess. In a study of 136 first pregnancies and deliveries – 30 prepared by hypnosis, 51 prepared by relaxation without hypnosis, and 55 unprepared controls – Furneaux and Chapple found some shortening of labour by the hypnotised women, particularly for the first phase. Based on questionnaire responses, the hypnosis group found the labour less unpleasant than the unprepared control group, whereas [surprisingly!] the relaxed group found it more unpleasant than the controls. It appears that something about hypnotic relaxation interacted with the effects of relaxation alone to produce a more favourable outcome. (p. 111)

In other words, in this study, relaxation training alone apparently backfired and was unhelpful, whereas hypnosis shortened labour and made it a more pleasant experience. In some hypnotherapy approaches, additional coping techniques were employed, e.g.,

Another possibility is to displace the symptom to another part of the body. For example, the rhythmic contractions felt in the abdomen can be displaced to rhythmic contractions felt elsewhere in the body. August [one of the leading researchers in this field] suggests that the patient clasp her hands and tighten them with each contraction. Attention is gradually shifted from the painful abdominal contractions to the painless ones in the hands. A later suggestion that the patient need pay no attention at all to the contractions helps to complete the displacement of all feeling to the hands.

Another familiar hypnotic technique, “glove anaesthesia”, involves the woman’s hand being stroked during hypnosis with suggestions that it is becoming numb, so that the sensation of numbness can then be transferred from the palm of the hand to other parts of the body by touch.

Hilgard cites data from 850 consecutive cases of childbirth using hypnosis reported by the obstetrician August,

Major anaesthetics and analgesics were available to patients who requested them. Of the 850 cases in the hypnotic analgesia group, 58 percent required no medication whatever, 38 percent used only analgesics such as demerol, and only 4 percent (36 of the 850) requested either local or general anaesthetic. (p. 114)

August’s figure of 58% of hypnotised women giving birth without pharmaceutical pain relief, in his own care, is similar to that (62%) reported in a more recent meta-analysis (Cyna et al., 2004). Likewise, a Russian study of the Pavlovian hypnotic method published by Katchan and Belozerski in 1940 reports on 501 cases, in which 67% gave birth with “complete” or “partial” pain relief from hypnosis. Another study directly compared self-hypnosis to the Dick-Read method, and a control group,

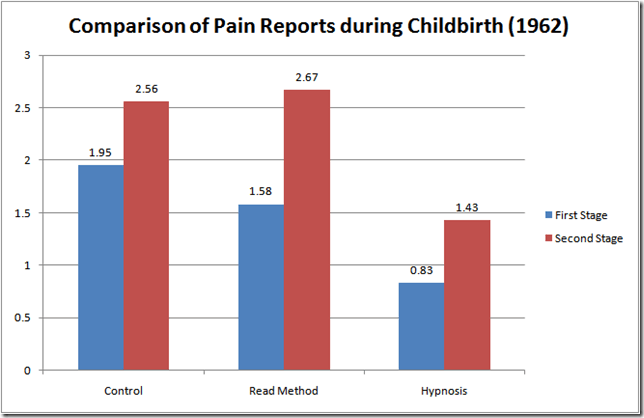

In a 1962 study of 210 pregnant women Davidson included a careful estimate of their felt pain. The women were divided into three groups of 70 each on the basis of preparation: first, a control group receiving no training; second, a group taught autohypnosis in preparation for labour; and third, a group taught relaxation by exercises and controlled breathing – the Read method. By assigning numerical values to the four levels of pain reported by Davidson – 0 for “no pain”, 1 for “slight pain”, 2 for “moderate pain”, 3 for “severe pain” – we have been able to compute a mean for each of her groups. In the first stage of labour, the mean for the control group was 1.95, moderate pain. Those prepared by physiotherapy [Read method] reported their pain as 1.58 – below that of the control group – but the autohypnosis group was lowest of all at .83. In the second stage, when all pains were reported as more severe, the control and physiotherapy groups were practically alike (at 2.56 and 2.67), close to the upper limit of the scale; the autohypnosis group, with a mean of 1.42, was still near the scale value for slight pain. Davidson concluded that the time spent antenatally in hypnotic preparation (averaging about 1.5 hours pre patient) was certainly worthwhile for the benefit produced. The hypnotic preparation appeared more successful in the relief of pain than the Read method, which shower no advantage over the control group at the time pain was most severe. (p. 115)

It is notable and surprising that the Dick-Read group, employing relaxation, actually reported morepain than the control group during the second stage of labour. That's consistent with the paradoxical finding of the component analysis by Furneaux and Chapple discussed above, which also reported that women taught relaxation techniques reported labour as “more unpleasant” than controls, who received no preparation. In other words, in both these studies, relaxation training appears to have been associated with increased pain and discomfort, whereas hypnosis was associated with improvements on the same measures.

The graph below compares the subjective ratings of pain reported by the 210 women in these three groups during the first and second stages of labour.

Hilgard’s conclusion, after reviewing these and the other studies available to him was as follows,

The evidence is clear that for many women hypnotic preparation can provide for a comfortable, participative labour and delivery. The mother is aware of what is going on and can assist in the birth process with a minimum of pain. The outcome appears to be good for the mother and the newborn infant, not to mention for the father, if he has shared in it all. The exact proportion of women who can benefit cannot be specified, but of those who wish to have their babies with the help of hypnosis, a substantial fraction are likely to be successful. (p. 116)