- Last Updated

- Posted by

- Meditation and Mindfulness, Relaxation Techniques

The Role of Awareness Training in Relaxation Therapy

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2011. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2011. All rights reserved.

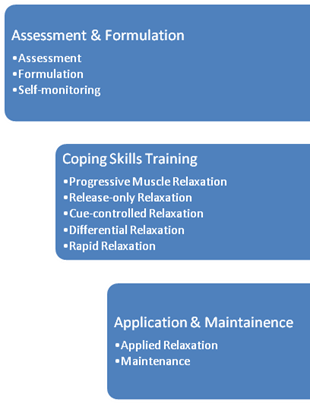

Training in Applied Relaxation can be divided into three broad stages (see diagram).

1. Assessment

Where information is gathered on the problem and its background. At this stage self-monitoring also begins, which tends to involve increasing awareness of automatic thoughts, actions, and feelings across different situations. This can often be seen as a form of “awareness training”, which potentially overlaps with everyday mindfulness of the kind acquired through Buddhist meditation practices. An important goal of this stage is to identify the range of trigger (“high risk”) situations in which the problem tends to occur, modulating factors that make those situations either easier or harder to cope with, and any “early warning signs” that tension or anxiety are beginning to develop.

2. Skills Training

A variety of coping skills can be learned in therapy and different CBT approaches tend to emphasise different ones, including a variety of different types and methods of relaxation. However, Applied Relaxation mainly employs a special technique of muscle relaxation known as “Progressive Relaxation” (PR), developed at the start of the 20th century by the physiologist, Prof. Edmund Jacobson. (See www.progressiverelaxation.org for an excellent sketch of his life and work.) Progressive relaxation was originally intended as a method of systematically training people to become more aware of the way they use their muscles, leading to greater relaxation. It therefore complements the goals of awareness training through self-monitoring.

3. Application & Maintenance

During this stage, the coping skills or relaxation techniques learned are systematically applied to the problem situations identified during the initial assessment and self-monitoring stage. This may be done first in role-play, through mental rehearsal, using the imagination, and, most importantly, through gradually more demanding tasks or situations related to the problem in the real world. Once the main problem has been dealt with adequately, emphasis may shift on to learning to cope with a wider range of situations. Finally, treatment ends by focusing on the prevention of relapse and maintaining positive gains over the longer-term.

Self-Monitoring and Awareness Training

This article will focus on the “self-monitoring” stage, as a means of increasing awareness, as this often leads to a reduction in the problem itself, just through mindful observation, without any specific coping skills necessarily having to be learned or used. People are generally quite unaware of the way they tense their bodies and becoming more mindful and self-aware can sometimes break the habit. Indeed, people generally complain of “being tense”, phrasing the problem in the passive voice (“I am tense”), rather than talking about “tensing” specific muscles (“I tense my neck”), using the active voice. Of course, this tension is usually automatic and happens without deliberate effort or conscious awareness most of the time. By simply becoming more aware of the process of tension, in everyday life, we can reduce its frequency and intensity, replacing mindless automatic tension with mindfulness. Becoming more aware of your bodily sensations, thoughts, feelings and actions, can be likened to learning to “listen” more closely to the wisdom embodied in your emotions. For example, Charles Darwin observed that we humans, like our animal ancestors, tend to automatically frown, by tensing the muscles of the forehead, when we meet with some difficulty or frustration.

“Subtle (“low-intensity”) early warning signs are to be treated as “cues to cope”, like a green traffic light, acting as a signal to immediately respond with the coping skills learned in the next stage, so that the problem can be repeatedly “nipped in the bud” at the earliest stage. The development of tension or anxiety can be seen as a sequence of steps, each one representing a “choice point” or opportunity to stop and think, or to engage in alternative behaviour. A good “socialisation” exercise, to help you understand the concept of spotting early warning signs and begin applying it to your own life, is as follows,

- “How do you know when other people are tense?” Brainstorm a list of observable signs that other people are becoming tense, e.g., in their mannerisms, facial expression, voice, etc. Try to make your list as exhaustive as possible. Common themes include frowning, staring, anxious speech, rigid posture or movements, etc.

- “How does that work?” Make notes on what physically causes the changes you’ve listed. For example, if you mentioned people speaking more rapidly, carefully consider how that might be caused by changes in their breathing or muscle use. When people frown, what muscles are they using? What other changes are associated with that? For example, when people frown do they also move their head and body differently, change their gaze, or speak differently?

- “When do you do that?” Notice where and when you do similar things with your body and behaviour. What does that feel like inside? What thoughts and sensations are you experiencing at the time? For example, notice where you are and who you’re with when you frown and what you’re feeling and thinking as you do so.

Think in terms of shifting your overall “orientation” or attitude toward your body, adopting a more mindful and body-centred way of life. If you like, you can treat this as a kind of behavioural experiment, taking a “trial-and-error” approach to body-focused mindfulness for a few weeks. It can be helpful to keep a personal journal, recording what happens and your reflections on the wider significance of what you observe for your individual problems and the rest of your life in general.

Keeping a Tally

One of the simplest methods of self-monitoring is to keep a running tally for a week or more of certain events. For example, you might simply tick a page in your diary to keep count of how many times you notice tension creeping into your muscles each day. You might also focus on counting the number of times you tense specific groups of muscles, such as your forehead, neck, jaw, or shoulders, etc. Doing this will help you keep a very simple measure of your progress as you’ll be able to see whether the habit of tensing muscles decreases in response to learning relaxation coping skills. It will also help you to become increasingly aware of the typical trigger situations and times of day when tension is most common. Finally, it usually leads to increased self-awareness of the “early warning signs” of tension, which you will inevitably find yourself on the lookout for. This will tend to make you more aware of your muscle use in general, throughout the day, as long as you continue to deliberately monitor your automatic behaviour or keep a tally.

Frequent Self-Rating & Running Log

Another good initial strategy involves self-rating your level of tension (or anxiety, anger, etc.) from 0-100% and then noting down in a running log what specific signs of tension you observed that led you to give yourself that specific number as a rating. This should be done carefully, and treated as an opportunity to patiently reflect on your thoughts and feelings, etc. To put it another way, you might pose the question to yourself: “Why didn’t I rate my tension as 0%?” and note down the signs (“cues”) that your self-rating was based upon. How often should you do this? Initially, it’s a good idea to do it frequently throughout the day, but particularly at times when you notice tension or other problems occurring. You might get into a routine of rating your tension every other hour throughout the day, or place post-it notes around your home or workplace as a reminder to self-rate whenever you notice them.

Self-Monitoring Record Sheet

A slightly more elaborate method, used in standard Applied Relaxation, involves keeping a simple self-monitoring record sheet with the following information,

- The date and time when the tension occurred

- The situation where the tension occurred

- The intensity of the tension or anxiety, rated on a simple 0-100% scale

- The earliest reactions spotted, i.e., early warning signs of tension such as starting to hunch your shoulders, or fidget with your hands or feet, sensations of pain in specific areas, anxious thoughts, etc.

A special effort is made to spot early warning signs of tension and record them, so that the habit can be interrupted at the earliest possible stage. Eventually another column can be added to record what was done in response to the early warning signs of tension, i.e., what specific coping skills were used, followed by a re-rating the level of tension 0-100%. In other words, you should eventually begin to record your level of tension immediately before and after using relaxation techniques, so that you have a record of how effective your coping has been.

Mental Imagery Rehearsal

Mental imagery techniques, which make good use of the imagination, can also be powerful ways of heightening self-awareness. In therapy, it’s common during assessment to ask the client to close their eyes and relive a recent event, describing their responses in detail, with the aid of prompts from the therapist, and perhaps in slow motion. Sometimes the client might be asked to imagine themselves at the point when tension or anxiety was first noticed, then to go back a few minutes and relive in detail the events, and their reactions, immediately preceding the full problem. This helps to raise awareness of the sequence of reactions, including early warning signs, and to take away the “automatic” feel of events. Likewise, the client may be asked to deliberately, in slow motion, make themselves tense or anxious, in the way they normally do automatically, and then to remove the feeling again several times in a row, in order to help them study the sequence of their reactions: thoughts, actions, and feelings. In a sense, tension-release exercises, such as Jacobson’s “progressive relaxation”, perform a similar function by allowing people to tense muscles systematically and study the sensations in detail – the goal being to raise awareness of their “muscle sense” and reduce automatic tension in daily life.